“An enemy is someone whose story you have not yet heard,” advised my dear friend Rabbi Arthur Gross Schaefer to his young son Avi, of blessed memory.

Storytelling is at the heart of Peter Brook’s deeply intimate and yet universal theatre as it should be to everyday life on and off the stage. Such was The Mahabharata (1985) and remains with Battlefield (2015), recently performed at The Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills CA.

In a town more noted for the Oscars, Disneyland and terminal traffic, the 1987 Los Angeles Festival production of Mahabharata, directed and written by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne, based on Le Mahabharata by Brook, Estienne and Jean-Claude Carrière continues to be a cultural signifier. One remembers with whom one suffered bleacher burn over the course of 9 hours watching the tales tangling in epic proportion and spotting the cast in costume walking through the sound stage “lobby” at numerous intermissions. Despite criticism that the longer work is an example of blatant cultural appropriation, as Rustom Baruch has charged, the experience of the theatrical event continues to be resonant to me in its many forms (book, film, stage).

It is a luxury to “check in” with what has also endured for me as a ritual experience. As if the longer work was my first “dose” and Battlefield is the “booster”; in between I have logged in 3 decades of hopefully conscious human development and an appreciation of theatre’s capacity to engage individuals in a personal and socially transformative experience. It was an opportunity to assess how have I fared on the destiny-o-meter. How many times did I make the same mistakes? Is there still a chance to clean up my karma? Who is my “Krishna”?

Thus, it is with this great anticipation that I welcomed the opportunity to attend the recent production of Brook’s Battlefield and welcomed the post-show Q & A set up by The Wallis’ Artistic Director Peter Crewes with the cast: Toshi Tsuchitori, Karen Aldridge, Sean O’Callaghan, Ery Nzaramba and Jared McNeill. Tsuchitori is an accomplished musician who has worked with Brook for decades. Audience members self-identified as whether they saw The Mahabharata or not. One audience man who had not, was delighted to see the tales he was told as a child embodied before his eyes; his experience seemed undiluted by aforementioned charges of cultural appropriation.

Ah-Jeong Kim, Professor of Theatre History at Cal State University, Northridge, joined me for the show and reported drifting into a deep silence as the last pat of Tsuchitori’s hands on his djembe took actors and audience into a natural stillness. “The music turned Battlefield into something bigger than a story-telling narrative drama—it was a ritual. I felt improved through the meditative experience at the end,” she noted.

The rehearsal process was one of the areas of the audience’s interest. The cast seemed somewhat hesitant to go into detail, citing that Brook has his very specific exercises to ready his actors. This is well documented in (son) filmmaker Simon Brook’s 2012 film The Tightrope in which Brook the elder is captured through stealth effort (5 hidden cameras) training actors in what Professor Kim refers to as his “rigorous process” during a 2-week workshop. Precision and communication, and an avoidance of “micromanagement” are at the foundation of his style. The Battlefield cast stated that “listening to the stories with others” is at the basis of their improvisational ensemble development.

The actors cast interstitial stories like the dice game from which the battle emerged, helped by a shift of a long scarf or Tsuchitori’s drumbeat and lighting to deliver many more characters than their number. According to Professor Kim, there was “an organic harmony.” Brook aims to “create a garden” through pure, clear, direct storytelling. The cast reported working “…’til we make it right” to become “one storyteller.”

“I thought Peter Brook’s Battlefield was a masterpiece, Professor Kim notes. “The somber opening scene depicting the aftermath of the war between the Pandavas and Kravas reminded me of The Persians by Aeschylus. It exuded that kind of sense of loss on a Greek epic scale.” Her research focuses on intercultural theatre, Asian theatre, and theatre history, and. Kim’s book, The Metacultural Theatre of Oh Tae-sok (1999) received the 2001 Korean Literature Translation Award in Seoul. Over the past 25 years, Kim has conducted workshops, talks, and given papers in Korea, China, England, and the Netherlands.

“Like many others, I’m assuming, I wondered why Brook revisited Mahabharata three decades later and especially in view of the negative criticism from India. Though representing “Indianness” was obviously never his goal, what is he trying to say through Battlefield? Then, the answer came to me: that the core of Indian epic is there in the eternal query into dharma (truth).

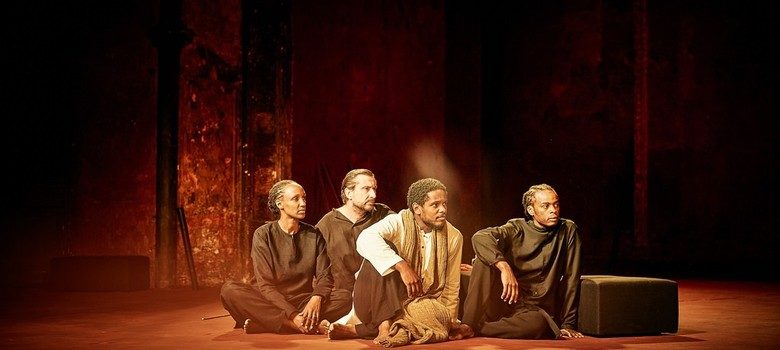

From left: Sean O’Callaghan; Carole Karemera & Ery Nzaramba in US Premiere of Battlefield C.I.C.T.—Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, Based on The Mahabharata and the play written by Jean-Claude Carrière Adapted and directed by Peter Brook and Marie-Hélène Estienne. Photo: Richard Termine

“Destiny and justice are mutable notions where certainty of death is the only sobering truth. The Hindi epic, through the wisdom of Bishima and his calm acceptance of destiny, are a good reminder for those of us–deeply torn and in trouble—that the itihasa (history) of Mahabharata continues in the 21st Century. To me, that is Brook’s gift back to India and the world.”

According to Brook, “We wanted to concentrate on one thing only,” he says. ” … What is the position of the great leader who realizes that he has done what he set out to do? He has won.” In the wake of this carnage is where Battlefield begins. While the press material stated that the piece was inspired by the current civil war in Syria, this was never mentioned even during the Q & A. Likely, the piece will resonate with many more conflicts of our times, past, present and, sadly, future. But this is karma, too.

Professor Kim added, “The connection Battlefield makes with the contemporary situation (in Brook’s words, “the harsh conflicts of today”) conveys well.”

I couldn’t agree more! Projecting the press material into the current state of the USA political climate: How often has “he” told us, “’She’ lost.” When will [his base], the ones who “won” and who now stand a great chance of being devastated by his policies, say, like Brook’s Yudhishthira, “‘Victory is a defeat’”? The losers are only now beginning to wake up to realize “‘They [We] could have prevented that war.’” Is resistance enough? I wonder, in 2018, will a new leader emerge to “find a way to rule over a divided people? How do you rule justly after such a battle? How do you navigate through the world where good can exist within evil, and evil within good?”

Welcome to the Kali Yuga!

No comments:

Post a Comment